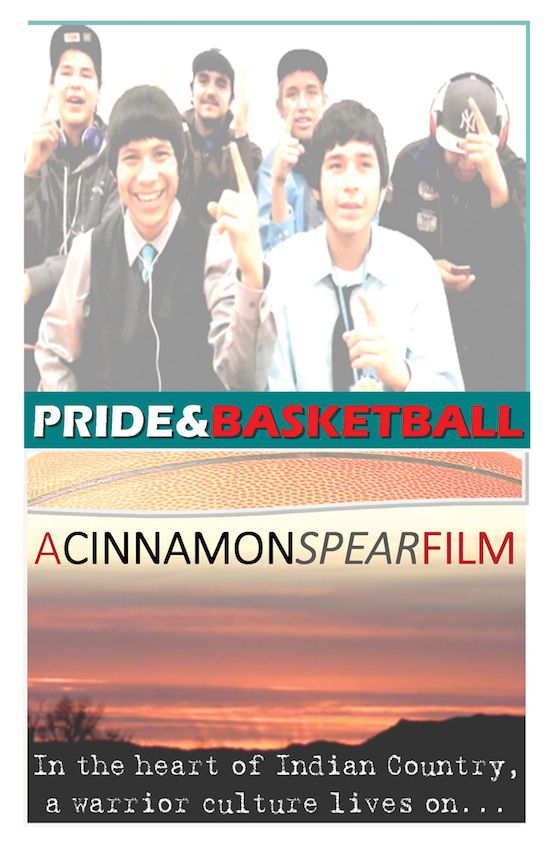

Cinnamon Spear of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana, wanted to document this pride and lifestyle of basketball. Although the documentary portrays the boys’ basketball team in Lame Deer, MT, she speaks for every reservation with her story. What started out as a thesis is now a breakthrough documentary that has already established a fan base throughout Indian Country and will soon hit the shelves.

We reviewed the short documentary and chatted with Cinnamon Spear about her purpose for the film and why it’s an effective option of educating uninformed individuals around the country.

What is your documentary about?

On the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, basketball is more than a game. It is our lifestyle. “Pride & Basketball” is the first film exploring the interesting and serious dynamic between high school boys’ basketball and warriorism- from an insider’s perspective. The game brings individual, familial, and communal pride to the residents of Lame Deer, Montana; this 32-minute piece highlights that. It also reveals how historic rivalries between neighboring tribes and non-Native race relations are relived on the court. This unprecedented release gives insight to how it has become a culture within a culture to develop the love for basketball at a very young age- because this is where we get our glory. The film further provides testimony to how some basketball stars live life, or remain in death, with a legacy that precedes them. As the viewer will come to find, the basketball court is one of the only places where Native children are truly praised and empowered, where socioeconomic status bares no relevancy. “It’s you against me; and I’m better than you.”

What inspired you to create a documentary on the pride of basketball on your reservation?

More academically, Native Americans have been burdened with misrepresentations for centuries, dating back to the earliest accounts of the “New World” documented by European explorers. Non-Native drawings and writings have been the basis for creating many harmful misconceptions that remain stubbornly embedded in the American psyche. Society possesses varying degrees of what David Treuer, an Ojibwe writer and critic, calls an “exoticized foreknowledge” due to these romanticized images that have flooded the American mindset by Hollywood and mainstream media. Most recently, music artists and the fashion industry have taken to horrid accounts of cultural appropriation. I believe I had gone to Dartmouth College as a representative from the Northern Cheyenne Nation. I developed my thesis, entitled Northern Cheyenne Pride, as a direct response to the ages of misrepresentation that have oppressed Indian people. Only recently, Natives have begun to address institutionalized racism utilizing forms of mass communication such as multimedia, social media, and video. My work with the award-winning documentary filmmaker and Indigenous activist, Alanis Obomsawin (Abenaki), has allowed me to understand the accessibility and power of film. This piece is my personal attempt to combat the aforementioned inaccurate, preconceived ideas. My film work is a solid example of positive self-representation that disassembles popular ideas and reveals the true complexities of real life for members of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe living on the reservation in southeastern Montana. I chose the topic of basketball purposefully, to rejuvenate a sense of pride in my community by simply highlighting who we are and what we are doing as a people, and putting these images back in front of them. I want my people to see themselves and their relatives “on screen,” and not the careless, manufactured Hollywood version that too often fills the space in front of them.

Why do you think pride for basketball is so strong on your reservation?

Traditionally, our tribe was politically governed by seven warrior societies and young men were recognized and honored for warriorism, advancing to a level of stature that could never be taken from them, despite any future social failings. In the post-colonial era, I have witnessed how the basketball court has transformed into that modern-day battlefield where our male youth are acknowledged for bravery and leadership. Basketball has the ability to make our boys, families, and entire reservation proud. Being one of few who has come from the reservation and achieved in higher education, at an Ivy League level no less, I am constantly told by members of my community that, “We are proud of you!” But I wanted to use my Master’s thesis as an opportunity to turn around and tell the members of my community that they are special, beautiful, and I am also equally proud of them.

What were the reactions of non-Natives who watched the documentary?

In the Upper Valley, I screened at a high school, at Dartmouth College, at community gatherings, and through churches. Off the reservation, the film evoked so many questions and such a desire to learn more! The post-film discussions lasted anywhere up to twice as long as the film itself! People were so incredibly touched by our story and engaged by our style of ball. There was one man in particular who said, “For those boys to disregard whatever is going on around them, in their homes, and step foot on that court and play like that- that’s a miracle! And for you to capture that, put this together, and be standing here in front of us today- that is also a miracle!” I can tell that I’ve definitely touched the non-Native viewer. Many were brought to tears. At home, I know that I have made those boys, their families, and my whole tribe proud as well.

Why did you think it was important to document the love of basketball on your reservation? On any reservation?

I have screened it several times in and around my home community. It was incredible for me to see the way the players would get nervous when they saw themselves talking on screen, but totally enjoy the basketball highlights of their games. I created this film so that it may be shared between families and passed down through generations like many of our collective memories and tribal stories have been. The circulation of this film at home is meant to intentionally influence and redirect a collective, in attempts to create a self-realized path of hope and optimism, inspiring our sense of self, which ultimately helps my people feel pride in who they are.

[This story was originally published in Native Max Magazine‘s Anniversary Issue.]