Select a subscription plans

You need a subscription to access this content.

Remember a time when your family would gather for a photo? It’d be a disposable camera, and someone always treated each photo taken as if it were the only way anyone would ever get to remember that moment. In many ways, it was. Capturing a piece of personal history; birthday cake with cousins, grandpa laughing, grandma holding her grand baby for the first time, siblings exhausted at the state fair but posing for a picture anyway. There were only so many shots to get the right photo and no way to see if the shot captured was the one intended. In the 90’s people would take the camera to a drug store and wait a week to get the film developed. AI is taking the web by storm. Where does Native fashion, history and identity meet in the crossroads of this growing technological capability?

Realistic AI generated photos were not on most people’s 2023 bingo cards. But in January 2021, DALL-E launched a free text-to-image Generative Pre-training Transformer (GPT), which is a form of AI. At first it was producing grainy, silly images. However as users began to utilize the technology, it learned how to create even more realistic images in a short span of time. Now it is to the point where even professional photographers are having trouble differentiating real images from the AI generated ones. In 2023, there are now many platforms providing GPT text-to-image generators producing realistic imagery.

So what’s the big deal with a computer program producing a picture based on textual input? Well, it’s much more complex than that. AI uses patterns and designs created by human artists and real photography. This means that when the program produces an image, the work is based on patterns and designs created by real artists. Being aware of intellectual property theft, and appropriation of traditional designs becomes more difficult to do in the world of AI. As usage increases, the ability to produce more realistic and more precise images also grows.

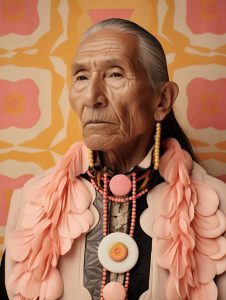

Native Max Magazine reached out to two artists who are vocal about AI use in the art and fashion industry. Our interest is to explore what this could mean for Indigenous artists and designers. Additionally, we did some research of our own, using free AI tools like Imagine to see what type of Native fashion imagery we could create with text. The results, intriguing and somewhat eerie for even those who understand how the algorithms work. While discussing the AI ability to create amazing and realistic imagery, there was a shared opinion by both artists: AI art is not Native art nor is it photography.

Shane Balkowitsch is a renowned American wet plate photographer based out of Bismarck, North Dakota. He has work permanently curated in the U.S. Library of Congress. Balkowitsch holds deep rooted concerns in the manipulation of history and context with images being produced by AI generators. “There is no distinct style. All the biases and stereotypes about Native Americans… AI is just melding everything it learns about Native Americans all into one image,” he explains, “You don’t get the kind of concrete differences that you do with the [574] federally recognized tribes.”

Native erasure is a commonly discussed topic, and a challenge Native communities are working to overcome constantly. Finding that Native identity is often appropriated and misrepresented by those who are not from tribal communities, AI sparks a different worry in photographer Balkowitsch; “As a historian these photos are in the wild. Once posted there is no control over what happens to them”.

As time proceeds and the algorithms continue to evolve and learn more about distinctions that can be made stylistically; clarity will come forth as quickly as it has in the imagery since it launched just over two years ago. Even a year ago, the images produced weren’t as detailed or realistic, we knew we were looking at fake photos then. But after just a year of learning from user input, the platforms are producing images that even professional photographers are struggling to distinguish. Is it real or is it AI?

Ethics is quickly becoming a central matter in developing protocols for usage. With viral images like the ones created by Marlena Myles (Spirit Lake Dakota/Mohegan/Muscogee), a self-taught St. Paul, Minnesota artist; It raises the question about how to use this technology with accountability and keeping intact ethics. Myles’ professional work includes children’s books, augmented reality, murals, fabrics, animations and her first permanent site-specific augmented reality public art installation known as the Dakota Spirit Walk. Art and technology are a match made in the stars, “We’ve adapted and innovated traditionally. And we can continue to use these tools to encourage that,” says Myles.

Myles started playing with the Midjourney bot, about a year ago. “I’ve seen non-Native people try to create Native art. But they don’t have an accurate perception of who we are.” She reveals that it all started out of a desire to see more representation. Expressing the constant historical placement of modern natives, she feels that “modern tintype imagery is still showing from a historical perspective.” Myles explains that growing up she didn’t see representation in the media as a Native person. Platforms like Native Max Magazine, and shows like Reservation Dogs are working to increase representation and visibility but in Myles’ opinion, some visual representation is still lacking. “I was using it as a way to see native people on the moon or on the Titanic.”

“Everything has a spirit, even AI.” Myles feels it holds a sort of, “non-human”, “collective” spirit. It’s important to Myles that we share, and she emphasizes that, “AI is not native art or content.” When using platforms like Midjourney, Myles explains that, “It’s AI art, it’s just a native person using a tool to express a perspective.” Native and non-Native users input words in English and have the bot produce what it has learned is “Native American”. This may open up one’s mind to new questions about how to use these AI tools in a good way. According to Myles, this is a “small fragment of our complex realities,” and many Native users are, “trying to honor traditions, and merge with futuristic tech.” Native identity and existence is not delegated to the past, Indigenous people are modern people.

As the AI image generators continue to learn, unforeseen consequences may begin to unravel themselves. For Balkowitsch’s award winning and famous wet plate imagery style, he’s already experiencing how the AI is taking examples of his work. It is reproducing new images sourced from his own. He feels that the AI images are, “simulating heritage with technology.” Worse yet, Balkowitsch foresees the possibility of destroying the validity of historical image documentation.

“What is both interesting and at the same time terrifying is that these applications improve at an exponential rate […] A year ago, it would be hard to find a convincing A.I. generated portrait image. Today, even the field’s experts are easily duped,” Balkowitsh wrote in an article for PetaPixel.

Using and training the technology could be adding to Native erasure later down the line. In the PetaPixel article, “AI Imagery May Destroy History As We Know It”, Balkowitsch shares AI generated images prompted in Midjourney by Steve Lease. One of the images is an incredibly realistic looking tintype photo of a young girl. The image generated through the prompted phrase: “Tintype of lost New Mexico tribe circa 1800’s”, shows an eerily realistic historical looking image. Once one realizes the solemn and innocent face is that of a stereotypically depicted Native child that never existed, it leaves an uncomfortable feeling.

Using the AI technology is allowing Native users like Myles to depict Native representations and perspectives in their own English words. Regarding Native erasure, there are many concerns that have existed before AI went mainstream. “We cannot stop outsiders from making stories and writing about Native people through fantasy bias and romanticism,” Myles states, “I make my own art, the AI is for fun and a creative outlet. It is not for financial gain.” If Native and non-Native users clearly label AI art, then the question and worry of ethics and usage are greatly decreased.

On the other hand, AI images are being produced and shared under the guise of being real and/or not clearly labeled as AI generated. “That’s my problem as a historian,” Balkowitsch says, “When someone brought this picture of a young Native American girl into the world… It’s in the wild.” With the Neanderthal image attached to his name through an AI prompt, the concern is that the image can be indexed with Balkowitsch’s name. And by that circumstance, someone may confuse that image with actually being his work, or something he created. But Balkowitsch is adamant that for himself, and many artists in this position, “I had no say in it whatsoever.”

Myles knows the technology is accessible to the public now, and it’s going to be used regardless of general comfortability, “It’s perspective built. We can’t stop outsiders from talking about us.” Myles offers that, “teaching people to respect it, having protocols,” can really ease the threat. “Treat it with some humanity,” she said encouragingly.

As with any publication, citing sources is highly appreciated and with AI there is no difference. “Watermarking AI generated images, as AI generated is good. But other ways are misleading. I don’t agree with watermarking it as real art, and it should be marked as AI art. Even Photoshop has AI generation,” she says. Balkowitsch echoes the same sentiment, “Without credit it’s unethical. It’s destroying history.”

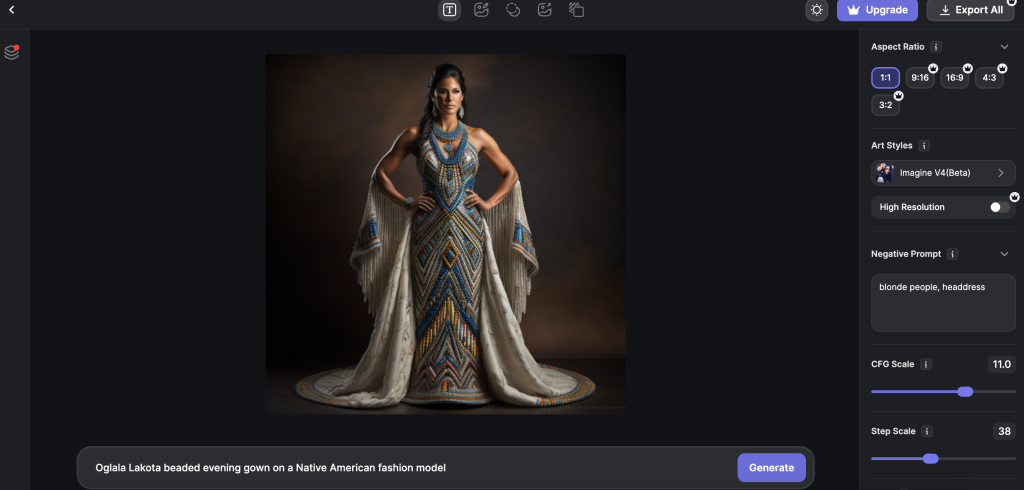

These conversations further sparked curiosity with the Native Max team. So I decided to investigate AI image generation firsthand. Platforms like DALL-E and Midjourney require payment, but there are free platforms that can be found with a Google search. After searching through free options, I decided that Imagine – AI would be a great place to test out some text prompts, and see what type of Native fashion could be generated.

At first I began with some simple prompts: “Oglala Lakota beaded evening gown on a Native American fashion model” note that I added a negative prompt to exclude: “blonde people, headdress”. This wasn’t to exclude blonde Native depictions, because we all have a blonde Native cousin somewhere… I added this because at first it was only depicting images of caucasian presenting blonde women wearing headdresses. Immediately the images were propagating with a pattern that evoked the ‘white gaze’. Thin bodies, stereotypical facial features, and a lot of High Plains region looking models.

After the first test, I wanted to see what type of modern fashion looks could be produced and what the variations would look like between different defined indigenous groups using the following prompts: “different coastal salish design bodycon suits on native american models”, “different inupiaq design bodycon suits on native american models”, and “different lakota and dakota design bodycon suits on native american models”.

The next test was to see if it was possible to depict specific designer styles into an image. A personal favorite of mine is ACONAV by Loren Aragon. So I began to test the bot, at first the image produced wasn’t very detailed, but I tried again and the second time it seemed to get closer. At this point, I decided to no longer teach the AI about Loren Aragon’s work, but maybe someone else will further that in the algorithm.

AI image manipulation is easily predicted to increase around the world. What does this mean for Native fashion? We will continue to learn as the technology does. Currently Myles has designers reaching out to her to recreate some of the designs in her viral AI images. “All designers copy each other. Fashion in a sense is derivative of one another,” Myles mentioned, “Everyone has ribbon skirts, that’s a bigger issue than AI, and that stems from pan-Indian identity.” Maybe she’s right, “people need a bit of compassion. We love to criticize everything. Why not just show respect. Maybe it’s [AI art] just to make people feel good. The power of art.” Myles added that an AI fashion week is coming. She shared concern that there are some who are acting as, “gatekeepers to indigenous futurism,” but she says, “it isn’t just comic books and card games. It’s using tech and code.”

Chatting with Balkowitsch and Myles shows that although the concerns vary, it’s clear that transparent protocols should be made to keep up with the tech. Myles says its “opening the door to modernize the IACA (The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990) and allowing us all to reflect the ways Native people produce things.”

Throughout this experience, I’ve also begun to question the ethics behind usage of AI, what is shaping modern Indigenous identity, and how we reclaim that in our rapidly changing world. Photoshoots from Native Max Magazine take hours to organize and put together, but the AI is producing similar styles of imagery within seconds. AI is learning faster than many of us can comprehend. Indigenous people are modern people. The need to protect the validity in historical imagery of Native peoples and thus the political identities attached to federal recognition, proves there may be a new set of challenges on the horizon.